Highest Weight Theorem

Similar to the $\sla(2,\C)$ case we may start with some weight $\l$ and some weight vector $x$ and apply the operators $\psi(X_j)$ and $\psi(Y_j)$ in any order to get some new weight vectors according to lemma. However, since $E$ is finite dimensional we must eventually get the null vector. Is there a way to start with some "highest" weight and work down to get all the others? Yes, this can be done, but it`s not as easy as in the $\sla(2,\C)$ case: First let us single out the roots $r_1=(2,-1)$ and $r_2=(-1,2)$ (with root vectors $X_1$ and $X_2$; it`s easily checked that all the other roots are linear combination of these two: e.g. the root corresponding to the root vector $X_3$ is just the sum of $r_1$ and $r_2$.

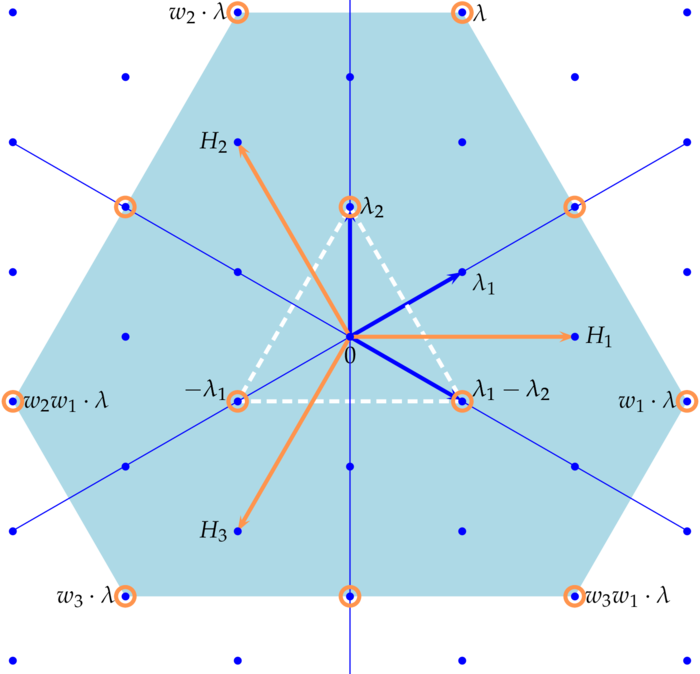

Let $\psi:\sla(3,\C)\rar\Hom(E)$ be a representation. On the set of all weights we define an order by putting: $\l_1\preceq\l_2$ if the difference $\l_2-\l_1$ is a non negative (i.e. $a_1,a_2\geq0$) real linear combination $a_1r_1+a_2r_2$ of $r_1$ and $r_2$ - we say $\l_2$ is higher than $\l_1$. If $\psi:\sla(3)\rar\Hom(E)$ is a representation and $\l$ a weight of $\psi$, then $\l$ is said to be a highest weight if for all weights $\mu$ of $\psi$ we have: $\mu\preceq\l$.

In the picture below the weight (0,0) is higher than any weight in the blue sector!

- There exists a weight vector $x\in E\sm\{0\}$ with weight $\l$.

- For all $j=1,2,3$: $\psi(X_j)x=0$.

- $x$ is a cyclic vector, i.e. the space generated by $\psi(X)x$, $X\in\sla(3,\C)$ is all of $E$.